How Ethical is Ethical Fashion?

Ethical Fashion is a big buzz word with the rise of companies and especially independent designers trying to distinguish themselves in the worldwide clothing market by claiming to be “ethical” to stand out and grab market share. Term as applied to the fashion industry, and that’s an important word industry, covers more than a few issues; working conditions, exploitation, fair trade, sustainable production and materials, distribution, the environment, and animal welfare. But many companies are focusing on “Organic” and “Sustainable” as the accessible the badges of the meaning of ethical fashion. This comes from an effort part to simplify or dumb down the message for mass consumption and in part to keep the consumers largely ignorant. Also, to play down all the issues concerning being ethical as is extremely difficult to claim to be fully ethical on every issue.

I am Abi Tyrrell and I own and run the independent designer business, RavenDreams Lingerie. Maybe the best way for me to talk you through this thorny subject is to show how my business sits on the ethical scale. A common phrase for stating a company is ethical is, “…designed, sourced and made in UK/US.”

Well, designed is easy! Most indie companies are kitchen table organisations. So the design process is done usually by the designer themselves. I carry a sketch book with me where ever I go and a drawing app on every device. “Sourced” is a little more difficult…

A company/designer can use silk, hemp, bamboo, or organic cotton or linen and claim to be ethical. But there is a confusion between sustainable and ethical. Those crops are all renewable which makes them sustainable but the way in which they are produced can make them unethical. If the cloth is made by employing chemical bleaching or dyeing that is harmful to the environment, or working conditions in the factories where the cloth is produced exploits its workforce, then that cloth/materials is unethical. When acquiring ethically made materials you have to explore the entire supply chain.

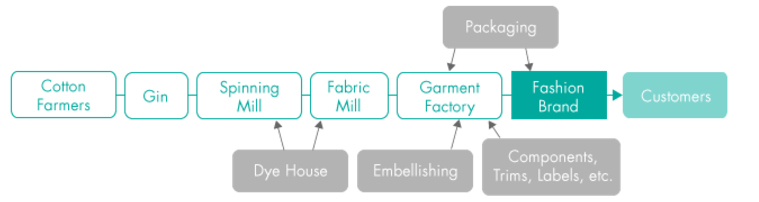

As you can see, a typical supply chain for a simple cotton t-shirt has a lot of elements in its makeup. Now to say that you have sourced ethical materials rather than go and check in person each of the stages and people in the supply chain personally, you can buy from a third party who has done that for you. They will have checked the certificates (of which there are a dozen or so organisations who will certify your products, factories and supply chains… for a fee) to ensure an authentic source. Those materials could be from anywhere in the world, but they will have been found and researched by a local company. For example, I buy my silks from Biddle and Sawyer who have the silks made and dyed to order in China. Face facts folks! China is where silk worms come from! There a number of really great suppliers. Offset Warehouse and Funkifabrics are two. Take Funkifabrics who stock fabric that is 78% recycled materials. Their claim is that everything is designed and printed in the UK. Does not say where the fabrics come from. So when a company says it was sourced in its own location, does not mean that it can guarantee the ethical standard of where or how it was made.

Ethical materials often come with a price tag that starts at double the price of normal materials and then go up! There is also no guarantee that the quality will be better either. There is often little choice in finishes (satin, velvet…) and what is available only in a handful of colours. As a lingerie designer, one of my most used fabrics is powermesh – the stuff that the wing backs of bras are made from. Currently, there are NO ethical versions of powermesh. Getting a hold of ethically made sustainable materials is rare and expensive. Which brings up another problem, how much will the customer be willing to pay?

Another harsh fact: consumers believe that quality should be inexpensive. In Indie + Design’s first blind review we saw how little the reviewers were prepared to pay for independently designed pants. When the price of 1 metre of fabric starts at £14.99 and with careful cutting you can get maybe three pairs of full briefs, add costs of notions (elastics and any extras like lace, bows, crystals…), packaging, postage. You can spend over half the price of the £10 that a person has budgeted to spend on materials alone even before you start paying for labour. So if you are paying higher prices for materials you need to cut costs elsewhere which leads to mass production. Buying materials in bulk brings the costs down and items “piece worked” in factories lowers the cost of labour making that £10 pair of knickers possible.

The argument of US/UK production versus China/India was eloquently discussed by Playful Promises. There are ethically checked and certificated companies all over the world. Not every factory is inherently evil. In an unrelated article on politics, one of the by-products was a reporter discussing working conditions in China’s biggest industrial parks who makes Trump ties. This factory was lauded as being ethical to the journalist who inspected the business in its showroom, but the worker’s own words tell a different story. Despite a company having certificates, there is now way of actually knowing if its claims are true. And this is applicable to everywhere at all levels of manufacture. I am sure you’ve all heard the stories of interns in fashion houses doing all the handwork of couture garments unpaid or for as next to nothing as can legally happen.

So while I can claim the title of an ethical small business with a focus on sustainability, who designs, sources my materials, and makes everything in the UK. The real facts are these. Although I design and make everything myself, I cannot guarantee that the materials I use are ethically made and only some are from sustainable resources. My ethics, as are the ethics of nearly all businesses, are flawed and marginal. To become completely ethical to the degree the public believes someone who claims to make ethical fashion, is cost prohibitive to the point that it would put us all out of business. Despite that to become fully ethical right now is unobtainable. The infrastructure and availability of materials simply aren’t there.

The moral of this story is caveat emptor. Cost is what controls the levels in ethical fashion. What the designer/company can afford being controlled by what the customer is willing to pay.